Bank Run

A panic among customers at a deposit-taking institution resulting in excess withdrawals beyond the available liquidity

Over 1.8 million professionals use CFI to learn accounting, financial analysis, modeling and more. Start with a free account to explore 20+ always-free courses and hundreds of finance templates and cheat sheets.

What is a Bank Run?

A traditional bank run occurs when too many customers withdraw all their money simultaneously from their deposit accounts with a banking institution for fear that the institution may be, or will become, insolvent. Although jurisdictions have deposit insurance schemes to cover depositors, the inability to use funds or a potential loss (beyond insurance coverage) may often outweigh the customer’s trust in their institutions.

Total customer withdrawal may overwhelm a depository institution’s ability to return funds as agreed, as many are held as demand deposits. In general, if a bank has insufficient liquidity (e.g., cash) and cannot convert enough assets to meet its obligations, it defaults. Regulators must then step in to ensure an orderly return of depositor funds and to mitigate a broader panic.

Institutions only maintain a small portion of their assets in fractional reserve banking systems as cash. The amount reserved for daily cash requirements is unproductive to generate a return for shareholders; thus, the majority of bank assets are held in available-for-sale or held-to-maturity instruments such as government bonds, loans, mortgage-backed security, among others.

An uncontrolled bank run can wipe out shareholders, bondholders, and depositors (beyond an insured amount). When multiple banks are involved, it may create a cascading industry-wide panic that can lead to a financial crisis and economic recession.

Key Highlights

- A bank run results from an excess of customer withdrawals beyond a deposit-taking institution’s available liquidity.

- The cause of a bank run varies, but inherently it is fear and loss of faith in an institution to return deposited funds on demand.

- A bank run may lead to a failure of the institution, requiring regulators and deposit insurers to take over to prevent a cascading effect and a broader systemic risk to the fractional banking system.

Why Does a Bank Run Occur?

The critical quality for any bank is trust. If customer trust is suddenly diminished or lost, it can create panic (whether rational or not). With global banking regulations, bank failures are not the typical cause of bank runs. A bank run most often arises from public fear pushing a bank into insufficient liquidity rather than actual insolvency. A bank run can push an institution into bankruptcy if the bank cannot maintain a regulatory equity requirement.

Managing daily reserves is a critical function of any bank, but as more customers than planned withdraw money, this treasury function can become strained. The greater the withdrawal beyond the planned reserve, the higher the risk of default. If customers perceive a rising risk beyond their individual comfort, it can perpetuate a cycle that triggers even more withdrawals.

A bank may limit the withdrawals per customer or suspend all withdrawals altogether as a way of dealing with the panic. A complete shutdown is a drastic measure taken in consultation with regulators, sometimes after the close of a business day.

On March 6, 1933, the US president instituted a national shutdown called a bank holiday, for one week, due to persistent bank runs. The stoppage allowed banks to access cash from other banks or the central bank and ensure withdrawal requests were honored after they reopened.

Bank Runs in History

Bank runs have occurred throughout history with the development of bigger and more sophisticated institutions. The general cause is a sudden reduction in the full faith and credit of the institution by its customers.

For example, the United States stock market crash in 1929 left the public susceptible to rumors of an impending financial crisis. There was a decrease in investment and consumer expenditure, which led to increased unemployment and a decline in industrial production.

A wave of banking panics worsened the situation, with anxious depositors rushing to withdraw their bank deposits. The simultaneous withdrawals forced banks to liquidate loans and sell their assets to meet the withdrawals.

During the Great Depression, many bank runs occurred, with news of each triggering a wave of others as customers rushed to withdraw their deposits.

As deposits are loaned out to other customers, the bank’s assets are not liquid enough to support the rush. With a cash shortage, banks had to call the loans or sell assets at rock-bottom prices to supplement the mass withdrawals. Historically, bank runs were rampant when banks were mandated to concentrate on a single location (or branch), limiting diversification and increasing the risk of failure.

One historical casualty of the banking crisis was the Bank of the United States in December 1930. A customer walked into the New York branch of the bank and asked to sell off his stock in the bank. However, the bank advised him against selling the stock since it was a good investment. The customer left the bank and started spreading rumors that it had refused to sell his stock and it was facing insolvency. Within hours, the bank’s customers lined up outside the bank and made withdrawals totaling $2 million in cash.

During the Global Financial Crisis, many institutions failed due to liquidity shortfalls, resulting in the highest failures[1] at US institutions in the last 20 years, with a combined total of $374 billion in assets at the peak in 2008.

In 2023, the failure of Silicon Valley Bank with $209 billion in total assets was the highest since the middle of the Global Financial Crisis, when in 2009, the total assets of all 140 bank failures totaled $171 billion. It is the second highest failure, the highest being Washington Mutual in 2008, with total assets of $307 billion[2].

The cause of this bank run was reported as a sudden $42 billion[3] in withdrawals by customers, overwhelming the bank’s liquidity and capital. The bank’s niche was banking for start-up businesses backed by venture capitalists associated with Silicon Valley. These businesses heavily relied on equity and cash injection, not traditional financing.

Silicon Valley Bank could not match the liabilities (customer deposits) to assets (i.e., loans, etc.) from this substantial clientele, so instead it purchased a large amount of marketable instruments to generate a return on equity. Unfortunately, the swiftness in deposit flight (originating from financing by venture capitalists) quickly overwhelmed the bank’s ability to sell available-for-sale assets and also raise equity to meet obligations.

Furthermore, with its held-to-maturity assets, due to a rising interest rate environment the value has significantly diminished. The bank would suffer a significant loss if it liquidated such assets, and cannot address its capital requirements by the sale of these longer term instruments. This is because any realized losses would further deplete the regulatory capital it needed to remain solvent.

Recovery from Bank Runs

After assuming office in 1933 as the 32nd President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a national bank holiday. The holiday allowed for federal inspection of all banks to determine if they were solvent enough to continue operations. The president also called on the US Congress to develop new banking legislation to help the ailing financial institutions.

In 1933, President Roosevelt gave speeches that were broadcast on the radio, assuring American citizens that the government would not want to see other incidents of bank failures. He assured the public that the banks would safeguard their deposits once they resumed operations and that keeping money in the bank was safer than keeping it under the mattress. Roosevelt’s actions and words marked the start of a restoration process where citizens would trust the banks again.

The Banking Act of 1933 led to the formation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The act gave the body the authority to supervise, regulate, and provide deposit insurance to commercial banks. The body was also responsible for promoting sound banking practices among banks and maintaining public confidence in the financial system. To avoid triggering a bank run, the FDIC performs takeover operations behind closed doors and reopen the next business day under new ownership.

Bank Run Mitigation Measures

In a situation where a banking institution faces the threat of insolvency due to a bank run, it may use the following techniques to mitigate the run:

Slow it down

A bank may slow down a bank run by artificially slowing down the process. During the recession in the United States, banks that feared a bank run would have their employees and their relatives make a long queue in front of the tellers and make small and slow deposits or withdrawals. This would help the bank buy time before the closing time. This technique has now been supplanted by “technical issues” that delay or stop transactions from completing in the era of digital banking.

The ideal solution is to work with authorities to access short-term liquidity, satisfy demands, or raise equity to meet demands.

Borrow money

When the bank’s cash reserves cannot handle the number of cash withdrawals, the bank may borrow money from other banks or the central bank. If they can be loaned a huge sum of money, this can prevent the bank from going bankrupt.

The Central Bank is sometimes known as the lender of last resort. This is a responsibility to safeguard the soundness of their institutions by loaning out money to struggling banks and prevent a wave of bankruptcies and the cascading negative effect on the banking system.

In 2023, the Federal Reserve announced a new short-term “Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP)” to backstop institutions requiring liquidity to meet obligations. The term sheet is recited below, with the US Department of the Treasury, in turn, guaranteeing the Federal Reserve for up to $25 billion under this program. Using the same 2022 capital ratio of approximately 12x at banks that the Federal Reserve oversees[4], the program translates to a potential coverage of approximately $300 billion in deposits.

Deposit insurance

Insurance on customer deposits guarantees participants that, should the bank go under, they will get their money back up to the insured amount.

Deposit insurance started in the United States after the Great Depression when the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was formed. The body restored public confidence in the banking system, and its mandate was to ensure customers get their money back if a bank becomes insolvent.

If a bank collapses, an insurer such as FDIC may facilitate a resolution, such as an acquisition by a bank with high capital reserves to backstop a vulnerable bank (and its customers). The customers can then access their deposits under the combined bank. A less desirable option is for the FDIC to seize the vulnerable bank and conduct an auction of the assets to raise funds to return to depositors. The sale proceeds cover amounts beyond the guarantee by the insurance fund. Any shortfall will be covered by a change in deposit insurance premiums paid by the industry.

Term deposits

As part of its treasury and balance sheet management, a bank can incentivize its customers to use non-callable term deposits and earn a higher percentage of interest on the money. As it’s non-callable, customers can only withdraw their money after the end of an agreed period and not on demand.

Term deposits effectively lock up a bank’s liabilities, so the bank can survive a bank run even if customers withdraw other deposits.

Additional Resources

Free Introduction to Banking Course

2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis

Is SVB the Next “Lehman Moment”?

Article Sources

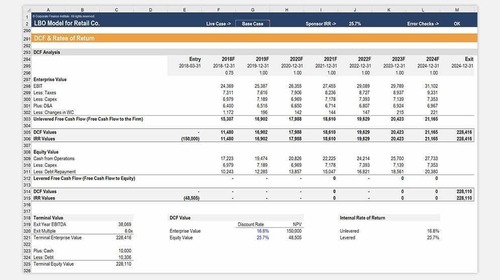

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in