- What is Venture Capital?

- How Does Venture Capital Work?

- Characteristics of Venture Capital

- 1. Illiquid

- 2. Long-term investment horizon

- 3. Large discrepancy between private and public valuation (market valuation)

- 4. Entrepreneurs lack full information about the market

- 5. Mismatch between entrepreneurs and VC investors

- Venture Capital Exit Strategies

- Venture Capital vs. Private Equity Investors

Venture Capital

A type of private equity investing that involves investment in a disruptive business with high growth potential

Over 1.8 million professionals use CFI to learn accounting, financial analysis, modeling and more. Start with a free account to explore 20+ always-free courses and hundreds of finance templates and cheat sheets.

What is Venture Capital?

Venture capital is a type of private equity investing that involves investment in earlier-stage businesses that require capital. In return, the investor will receive an equity stake in the business in the form of shares.

Companies that raise venture capital do so for a variety of reasons, including to scale the existing business or to support the development of new products and services. Due to the capital-intensive nature of starting a company, many venture-backed companies will operate at a loss for many years before becoming profitable.

Key Highlights

- Venture capital firms make private equity investments in disruptive companies with high potential returns over a long-time horizon.

- There are different stages of venture capital financing for companies depending on their phase of growth and objectives.

- Investors in a venture capital firm generate returns when a portfolio company is either acquired by another company or taken public through an initial public offering (IPO).

How Does Venture Capital Work?

Private equity investments are equity investments that are not traded on public exchanges (such as the New York Stock Exchange).

Institutional and individual investors usually invest in private equity through limited partnership agreements, which allow investors to invest in a variety of venture capital projects while preserving limited liability (of the initial investment).

Venture capital funds are run similarly to private equity funds, where the portfolio of companies they invest in generally falls within a specific sector specialization. For instance, a venture capital fund specializing in the healthcare sector may invest in a portfolio of ten companies focused on disruptive healthcare technologies and equipment.

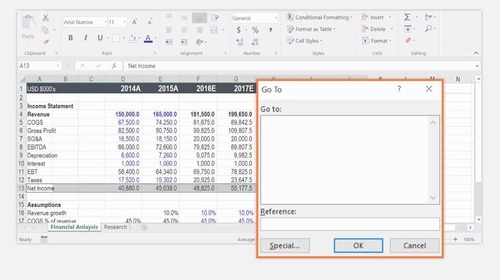

Structure of a venture capital firm (fund)

A venture capital fund is usually structured in the form of a partnership, where the venture capital firm (and its principals) serve as the general partners and the investors as the limited partners.

Limited partners may include insurance companies, pension funds, university endowment funds, and wealthy individuals, among others. Limited partners are passive investors.

All the partners have an ownership stake in the venture firm, but the general partners are actually hands-on. They may even serve as managers, advisors, or board representatives to the companies they invest in. These are called portfolio companies.

Profits from the disposition of investments made in the various portfolio companies are split between the general partners and limited partners. The general partners, who are also the private equity fund managers, usually get 20% of the profits as a performance incentive (often called a “carry”). They may also receive an annual management fee of up to 2% of the total capital invested.

The other 80% of any profits are divided equally (pro-rata) among the limited partners who invested in the fund.

Stages of venture capital financing

1. Pre-seed/accelerator-stage capital

Pre-seed-stage is capital provided to an entrepreneur to help them develop an idea. Many entrepreneurs interested in raising venture capital funding will enter business incubators (accelerators), which provide various services and resources for entrepreneurs to connect them with venture firms and networks that will help them develop their business idea and product.

2. Seed-stage capital

Seed-stage capital is the capital provided to help an entrepreneur (or prospective entrepreneur) develop their idea into an early-stage product. Seed stage capital usually funds the research and development (R&D) of new products and services and research into prospective markets.

3. Early-stage capital

Early-stage capital is venture capital provided to set up initial operation and basic production. Early-stage capital supports product development, marketing, commercial manufacturing, and sales.

This kind of financing will usually come in the form of a Series A or Series B round.

4. Later-stage capital

Later-stage capital is the venture capital provided after the business generates revenues but before an initial public offering (IPO).

It includes capital needed for initial expansion (second-stage capital), capital needed for major expansions, product improvement, major marketing campaigns, mergers & acquisitions (third-stage capital), and capital needed to go public (mezzanine or bridge capital).

Characteristics of Venture Capital

1. Illiquid

Venture capital investments are usually long-term investments and are fairly illiquid compared to market-traded instruments (like stocks or bonds). Unlike publicly traded securities, VC investments don’t offer the option of a short-term payout.

Long-term returns from venture capital investments depend largely on the success of the firm’s portfolio companies, which generate returns either by being acquired or through an IPO.

2. Long-term investment horizon

Venture capital investments feature a structural time lag between the initial investment and the final payout and usually have a time horizon of 10 years. The structural time lag increases the liquidity risk. Therefore, VC investments tend to offer very high (prospective) returns to compensate for this higher-than-normal liquidity risk.

3. Large discrepancy between private and public valuation (market valuation)

Unlike standard investment instruments that are traded on some organized exchange, VC investments are held by private funds. Thus, there is no way for any individual investor in the market to determine the value of the investment.

The venture fund may also not completely understand how the market values its investment(s). This causes IPOs to be the subject of widespread speculation from both the buy-side and the sell-side.

4. Entrepreneurs lack full information about the market

The majority of venture capital investing is into innovative projects whose aim is to disrupt the market. Such projects offer potentially very high returns but also come with very high risks. As such, entrepreneurs and VC investors often work in the dark because no one else has done what they are trying to do.

5. Mismatch between entrepreneurs and VC investors

An entrepreneur and an investor may have very different objectives regarding a project. The entrepreneur may be concerned with the process (i.e., the means), whereas the investor may only be concerned with the return (i.e., the end).

This can make discussions and general collaboration between entrepreneurs and investors challenging as they may have conflicting objectives around how the company should be run.

Venture Capital Exit Strategies

The process that allows venture capitalists to realize their returns is called an “exit.” Venture capitalists can exit at different stages and with different exit strategies. A proper decision on how and when to exit also significantly impacts the return of the investment.

1. Secondary market sales

Before the company goes public, the venture capitalists who invested in the earlier stage can sell their holdings to new investors during the later rounds. Since the shares have not been issued in the public exchanges, the trades take place in the private equity secondary market.

2. Acquisition

Another exit strategy is for another firm to acquire the investee company. The acquirer is usually a strategic buyer that is interested in the investee company’s growth and technology. Alternatively, a financial buyer could be an acquirer, although this is a little less common.

3. Initial public offering (IPO)

If the company is operating well and moving to the public exchange, the venture capitalists can take the IPO strategy by selling their portions of shares in the open marketplace after the IPO. There is usually a lock-up period after the initial offering that insiders (including venture capitalists) are not allowed to sell their shares. It is to prevent a decline in the stock price as a result of large numbers of shares flooding into the market. The length of the lock-up period is specified in the contract.

Venture Capital vs. Private Equity Investors

Although venture capital and private equity investors are both active in the private equity market by investing in and exiting companies through equity financing, there are still significant differences between the two types of investors.

1. Type of investee companies

One of the major differences is the type of investee companies. Private equity investors usually buy mature companies that may be undervalued for various reasons. The investee companies are not limited to private ones, as private equity investors can also acquire control of public companies and take them private.

On the other hand, venture capitalists target start-up companies that demonstrate significant growth potential with innovative technology but require capital financing. The companies are all private and relatively small in size.

2. Size of ownership stake

Another key difference is that private equity investors usually acquire 100% ownership of the target companies through leveraged buyouts (LBO), financing the cost of acquisition with a significant portion of borrowed money.

However, venture capitalists generally purchase no more than 50% of the investee company, mostly through equity investments. This allows the VC firm to diversify its investments into various companies to spread out the risks if a portfolio company fails.

Additional Resources

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in